Complying with the Law with F# and Event Sourcing

by Pedro León

This article is part of the FsAdvent 2025.

Thanks to Sergey Tihon for this wonderful initiative for the community.

Strings Digital Products

We are a software development studio with over 20 years of professional experience based in Madrid, specializing in critical

systems, event‑driven architectures, and domain‑driven design.

We work with clients from anywhere in the world, building robust, maintainable digital products that are designed to last.

You can read the spanish version of this article here

The Origin

In 2021 a law was passed in Spain that directly affects software developers who build invoicing systems.

For the first time in the country’s history the government regulated how a program must behave at a technical level, requiring

guarantees for invoice issuance through a law and its corresponding

Regulation.

Failing to comply with the technical regulation carries fines between €50,000 and €150,000 for software vendors.

For the first time a design flaw or a poor implementation could translate into a penalty of hundreds of thousands of euros.

Choosing Technology to Comply with the Law

Given this scenario we decided to be very conservative.

Better to go slow than to crash.

From the outset we made a key decision:

We would represent the legal requirements in such a way that we could compile them.

The F# compiler would be our ally.

If something didn’t compile, it couldn’t reach production.

If it didn’t reach production, it couldn’t generate an illegal invoice.

To achieve this we used two well‑known tools in this community:

We modeled each workflow using types, guaranteeing that it would be impossible to connect two steps incorrectly.

We put special emphasis on making incorrect states unrepresentable, following the principle of

“making illegal states unrepresentable” (Scott Wlaschin).We adopted Event Sourcing as an architectural pattern.

Our use case fits this approach particularly well: simply by using Event Sourcing we automatically satisfy three key legal

requirements: integrity, traceability, and immutability of business documents.For this we used Equinox and Propulsion on top of

Modeling the Invoice Issuance Workflow

Our service contains dozens of modeled workflows.

For this article we focus on one that is especially relevant from a legal standpoint:

the invoice issuance workflow.

Issuing an invoice involves generating an invoice from a draft invoice and a billing series.

The draft is the business document the user works on: they edit items, prices, recipient data, etc.

When they consider the draft correct, they can issue an invoice, which from that point must be immutable.

The invoice needs a number with very strict legal implications: it must be consecutive, coherent with the date, and unique.

There can be no gaps or duplicates, nor two invoices derived from the same draft.

Issuing an invoice involves three distinct aggregates:

Draft: the mutable prior business document.Serie: responsible for assigning consecutive invoice numbers.Invoice: the legal immutable invoice, identified by anInvoiceId.

Moreover, the three aggregates must change their internal state coherently:

- The

Draftmust not allow more than one invoice to be issued from the same draft. - The

Seriemust issue exactly the number that corresponds. - The

Invoicecannot be created twice with the sameInvoiceId.

Equinox guarantees transactionality at the aggregate level, but not across multiple aggregates simultaneously. Yet the process had

to be atomic from the domain’s perspective.

Because we couldn’t naturally use a database‑level transaction, we decided that the best approach was to model the transaction at the

domain level.

How We Made a Process Transactional Without Database Transactions

We have three aggregates in our Issuance process, and all three will receive events if the process succeeds correctly.

Just like a database transaction has a BEGIN and ends with a COMMIT or ROLLBACK, we do the same at the aggregate level.

The natural aggregate to perform this process is the Draft itself. We must ensure that when issuing an invoice from the draft it

can’t be started more than once.

If we looked at this in high‑level pseudocode, it would look something like this (the real implementation is more complex):

async {

// BEGIN

// Only the first process that invokes this line gets to proceed.

let! draftInIssuanceProgress : DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress =

draftId

|> DraftService.tryStartIssuance

try

// If the transaction has been started, the following commands will always succeed

// by design unless an exception occurs.

let! invoiceId =

SerieService.issueNextNumber (draftId, draftInIssuanceProgress)

let! issuedInvoice =

InvoiceService.issue invoiceId draftInIssuanceProgress

do! IssuanceInProgress =

DraftService.commitIssuance draftId invoiceId

return invoiceId, issuedInvoice

with

| ex ->

Logger.fatal "...." ex

DraftService.rollbackIssuance draftId ex

....

}

Our pseudocode shows a simulated application‑level transaction that works fine in principle, but there is an important detail that any

experienced programmer would have noticed.

It’s not a real transaction, and there is a subtle trap waiting to surface.

The trap, not obvious, waiting to appear at the most unexpected moment, is an error when attempting to do rollbackIssuance that will

leave the Draft aggregate in a state of started transaction forever.

We solved this with an external process using the Automation pattern and carefully tuning the timeout parameters of the

connection to our database:

On the one hand, in our Postgres

connectionStringwe set timeout parameters such asTimeout=1; Command Timeout=1; Cancellation Timeout=1which indicates that we wait 1 second to establish a connection or execute a command or read a response when a query is

cancelled or times out.On the other hand we have an external process that follows the Automation

Pattern and that has its own connection pool. If the process detects that

an aggregate has been in the started‑transaction state for more than 10.0 seconds, it rolls back the aggregate.

The combination of these times gives us confidence: after 10.0 seconds without changing the state it means that any execution of the

workflow has thrown a timeout exception with the database.

How We Modeled the Draft Aggregate to Behave Transactionally

After looking at the pseudocode of the process, let’s move to how we implemented it in an aggregate.

For this we modeled three new events that didn’t exist in the aggregate until that point:

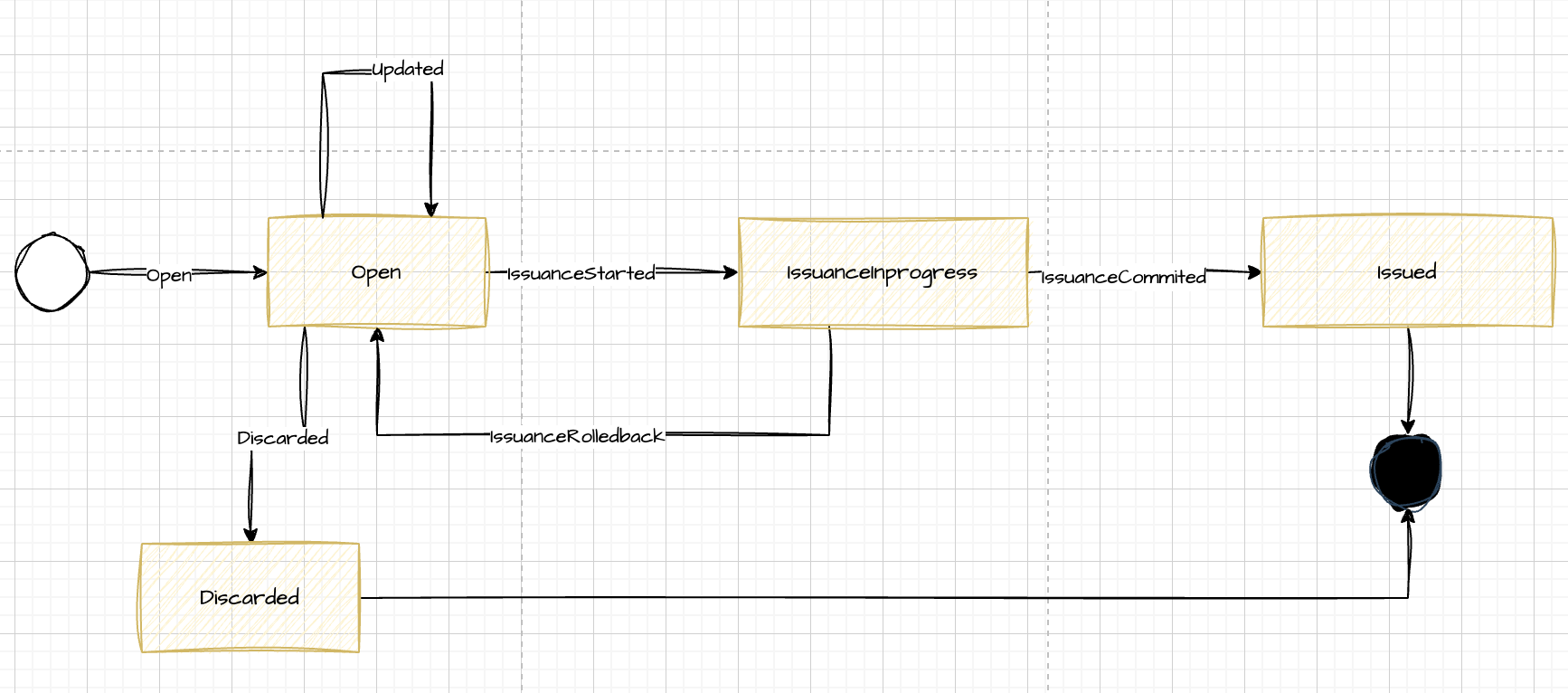

IssuanceStartedmarks the start of the transaction in the domain. Think of it asBEGINin database transactions.

This event can only be generated from theStartIssuancecommand.

Once this event is added to the aggregate’s stream, the state changes fromOpentoIssuanceInProgress.

This command can produce three possible results when invoking the aggregate’sdecidefunction (see

Decider):Ok [IssuanceStarted], which only occurs when the aggregate is in theOpenstate.Error IssuanceIsAlreadyInProgress, which occurs when the draft is in theIssuanceInProgressstate and indicates that the

transaction has already started and another one should not be started.

Error IssuanceIsAlreadyCommitted, which occurs when the draft is in theIssuanceCommittedstate and indicates that this draft

has already generated an invoice and therefore cannot be issued again.IssuanceCommittedis the aggregateDraftevent that reflects that the invoice issuance process has successfully completed.

Once this event is added to the aggregate’s stream, its internal state changes toIssuanceCommitted, and from that point the

aggregate accepts no further events.

Only theCommitIssuancecommand can bring the aggregate to this state.

This command can produce three possible results when invoking the aggregate’sdecidefunction:Ok [IssuanceCommitted {InvoiceId: InvoiceId}], indicating that the process has succeeded and storing the issued invoice

identifier (which helps us generate linking functionality in future projections).

Error IssuanceNotStarted, indicating that the aggregate did not start a transaction for invoice issuance.Error IssuanceAlreadyCommitted, indicating that the aggregate already generated an invoice previously.Finally, the

IssuanceRolledBackevent is the aggregateDraftevent that reflects that the issuance process failed for some

reason (bug, connection error with the other aggregates’ databases, or any other reason).

Once this event is added to the stream, the aggregate returns to theOpenstate (allowing the transaction to be restarted).

Only theRollbackIssuancecommand can bring the aggregate to this state.

This command can produce three possible results when invoking the aggregate’sdecidefunction:Ok [IssuanceRolledBack {Error: IssuanceError}], indicating that the process failed and storing the error for monitoring and audit

purposes.

Error IssuanceNotStarted, indicating that the aggregate did not start a transaction for invoice issuance and therefore cannot be

rolled back.Error IssuanceAlreadyCommitted, indicating that the aggregate had already generated an invoice previously and therefore does not

allow rollback.

All of the above can be seen in this diagram where the state transitions are the events labeled on the arrows and the internal state of

the Draft aggregate is shown in each box.

Modeling the Workflow with Types

Given all that, we move on to modeling the workflow.

By designing the signatures of the dependencies with types, we make ourselves safer, preventing unintended mistakes by forcing the

correct order through the types.

Our workflow’s signature is:

type TryIssueWorkflow =

CurrentDate

-> TryBeginIssuanceWorkflow

-> AssignNumberWorkflow

-> IssueInvoiceWorkflow

-> TryCommitIssuanceWorkflow

-> TryRollbackIssuanceWorkflow

-> DraftId

-> SerieId

-> Async<Result<InvoiceId * ReadModel.Issued, ProblemWith>>

TryBeginIssuanceWorkflow has this shape:

type TryBeginIssuanceWorkflow =

DraftId

-> DocumentSerieId

-> DateOnly

-> Async<Result<DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress, ProblemWith>>

If we look at the types we see that, in the correct case, it returns a DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress. This read model contains

the state change we discussed earlier. If the method isn’t called, the returned read model will not be in this state.

Next is AssignNumberWorkflow, a command that receives a Serie. It defines a clear precondition: it requires aDraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress (which is only obtained after starting the previous transaction) to be able to perform this step.

No data from the read model is stored, but it is requested as a parameter so that the sub‑workflows cannot be called in a disordered

way.

type AssignNumberWorkflow =

DocumentSerieId

-> DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress

-> Async<InvoiceId>

IssueInvoiceWorkflow will emit the invoice from an InvoiceId (which could only be generated in the previous step by the Serie

aggregate) and needs the DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress because it copies all the business document data.

type IssueInvoiceWorkflow = InvoiceId -> DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress -> Async<ReadModel.Issued>

CurrentDate simply returns the official date of the Iberian Peninsula when the invoice is issued. It is effectively a piece of data

with legal implications.

type CurrentDate =

unit -> DateOnly

Both TryCommitIssuanceWorkflow and TryRollbackIssuanceWorkflow we already know well, but we include them here to show that they

also request the DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress, making them callable only within a transaction. No read‑model data is stored in

this case either.

type TryCommitIssuanceWorkflow =

(DraftId * DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress)

-> InvoiceId

-> DateTimeOffset

-> Async<Result<DraftReadModel.Issued, ProblemWith>>

type TryRollbackIssuanceWorkflow =

DraftRollbackError

-> (DraftId * DraftReadModel.IssuanceInProgress)

-> Async<Result<DraftReadModel.Open, ProblemWith>>

With all of this we can easily compose a high‑level workflow from its dependencies, which are simply simpler workflows. In

practice, these workflows are materialized as calls to the public methods exposed by each aggregate.

In our case we follow the Service pattern per aggregate, as proposed by the Equinox Programming

Model.

These services are resolved via dependency injection in ASP.NET Core, which keeps the endpoint handlers clean, declarative, and

expressive at the same time.

We do not include the controller code in this article because it would unnecessarily lengthen the content. We’ll leave it as material

for a future post.

Conclusion

F# allowed us to turn legal requirements into compile‑time types, and that difference was decisive.

When an error can become a real monetary penalty, confidence in the design moves from a luxury to a necessity.

Many of the ideas I applied here are not new or original.

The emphasis on the domain, on making illegal states unrepresentable, and on explicit workflow modeling is deeply influenced by the

work of Scott Wlaschin, especially in Domain‑Driven Design Made Functional.

Likewise, the way we reason about system behavior through events, and separate decision from state evolution, directly draws from

Jérémie Chassaing’s work on Event Sourcing and the Decider pattern.

None of this would have been practical without tools that make it viable in real systems.

In our case, Equinox (and Propulsion) with MessageDb (thanks to Einar Norðfjörð) gave us the scaffolding needed to bring these

ideas into production safely, explicitly, and maintainably. My sincere thanks to their creators for proving that Event Sourcing in F#

is not just elegant, but industrial‑grade.

Sincerely, without a language like F#, with such an expressive type system and a semantics so aligned with the domain, I would have had

far less confidence implementing such sensitive legal requirements.

To the F# community: thank you for sharing knowledge, patterns, and real‑world examples.

This article is, in large part, a direct result of learning from you.

In a regulated system, that’s not just a technical decision.

It’s a way to sleep peacefully… and keep trusting this language and this community.